theartsdesk Q&A: Donald Runnicles | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Donald Runnicles

theartsdesk Q&A: Donald Runnicles

Scotland's greatest conductor explains why he's returned home

Saturday, 20 March 2010

Who's the greatest living British exponent of the late Romantic repertoire? Many would say Edinburgh-born conductor Donald Runnicles (b. 1954). Runnicles has spent the last 30 years quietly forging a formidable name for himself abroad, first, as a repetiteur in Mannheim, then as an assistant to Sir Georg Solti at Bayreuth, as guest conductor at the Vienna State Opera and, for the past two decades, musical director of San Francisco Opera. In 2007 the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra announced that Runnicles would return home to become their new chief conductor. This week he performs Strauss, Wagner and Mahler in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Aberdeen. He tells me how he came to work with Solti, how opera moulded his style and how a few remarks about how he was considering leaving America if Bush won another election got him into serious hot waters.

IGOR TORONYI-LALIC: Are you aware of the blog Where's Runnicles?

DONALD RUNNICLES: I am aware of that blog. Actually at the news conference in Glasgow when Ilan Volkov [chief guest conductor] and I announced our appointments, I met Mr Blogger. He was actually invited. He's a fascinating young guy. But I laughed the first time I saw it. I thought, "What kind of website is this?" As I'm sure you know, it certainly ain't about where's Runnicles. It's about where's Mackerras and where's this and where's that.

You realise we've all been asking ourselves this question for quite a while?

Now you know where I've been and where I am coming to!

Would you like the blog to change the name, now you're back?

Oh, I don't think I would ever meddle with press. That's up to them. I am just tickled by this blog. I've read it and what he wrote about the concerts I gave back in October makes very interesting reading. I don't mean that sarcastically. He gives great thought it. It's constructive writing.

Do you read critical reviews much of your own concerts?

Very rarely. I think the old adage applies: if you believe the good ones you deserve to believe the bad ones. What I try to do, certainly, in the run of an opera of six of seven performances is to steer well clear of reviews. I think any artist who says that they are not influenced by a review is in denial. If you read something specific to what your doing you may feel you should change it in the run of performance. I prefer to stick with what I believe in. After all, it's one person's opinion out of very many in the hall.

I've been going through some reviews of your concerts and they're mostly very positive. But they range widely as to what your distinctive style could be. One says you're "cool", another that you're "angry", another "sweaty".

I've been going through some reviews of your concerts and they're mostly very positive. But they range widely as to what your distinctive style could be. One says you're "cool", another that you're "angry", another "sweaty".[Laughs] I am all of those things and more!

You seem to be a conductor who has no single style that be encapsulated in one word; you change for every performance? Is that true?

To be objective about something that is so so subjective is difficult. I approach each and every concert with intensity, curiosity, also with a joy of knowing that it is unique and that it may be very different to the previous night or the following night. I suppose in some ways that is symptomatic of what one experiences more in the opera house than in a symphony hall. There are so many more moving parts in an opera. One is drawing all those strands together. There is so much more room on any given evening for variety and spontaneity - or, not even spontaneity, for pragmatic music making where you are gauging peoples' performances all evening. There is - in the best sense - something improvisatory about it that has become something of a trademark. I don't ever set out to do something different just for the sheer pleasure of it, though.

Is an eclecticism of style part of the modern conducting condition, do you feel? After all you all have to do so much traveling and switching between orchestras. It all seems quite different from the past where you had once orchestra and where each conductor had a more easily definable single style.

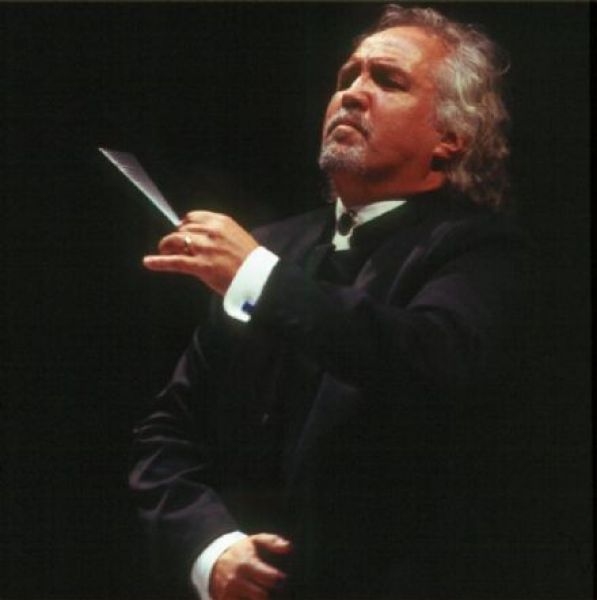

Is an eclecticism of style part of the modern conducting condition, do you feel? After all you all have to do so much traveling and switching between orchestras. It all seems quite different from the past where you had once orchestra and where each conductor had a more easily definable single style.It's a very good question. Traditionally, a music director's tenure today is anything between 12 to 14 weeks of a year. There are a lot of other weeks where there are a lot of other guest conductors. There is an even-ing out of the playing field. Conductors have to do less. That is certainly something of a mantra for me: less is more. That is not just confined to life as a conductor. And yet when I see and experience the Dudamel phenomenon, I suddenly realise that there is still room for that kind of - I don't mean this critically - larger-than-life, youthful flamboyance which has all of a sudden - like a young Celibidache (above left) - come on to the scene. He is like this Don Quixote figure who is fighting all these windmills and we're all swooning over this. We always swoon over this. I sometimes think have we come to a point where conductors are so interchangeable that there is a nostalgia for flamboyance, a nostalgia for reactionary music-making. One of my colleagues in Germany, for example, is well known - and is well aware of the fact that he is well known - for performances which are old-fashioned. It would appear that there are some orchestras who are nostalgic for (strange though this may sound) for pre-Harnoncourt days, pre-Herreweghe days. It is a fascinating subject.

Where you obliquely referring to Christian Thielemann (right) just then?

Where you obliquely referring to Christian Thielemann (right) just then?I don't believe that I mentioned any names [he says with a wry smile]. No, look, I am a friend and colleague of Christian's and I think I am stating it the way it is. His style is remarkable, utterly fascinating and captivating and genuinely quite old-fashioned. There is - and this is an appalling word - a market for this, like so many other things. We live in this globalised world where the world is flat - as Thomas Friedman would say. And there is now this almost reactionary reaction to things. Somehow people are eager for individuality, quirkiness and eccentricity.

So what has this got to do with me being sweaty, angry and cool. It is up to others really to describe what they think they're hearing and seeing. I know that what I seek now in my life, in my professional life, are relationships - whether with an opera company or a symnphony orchestra - where I feel that I am making difference, where I feel that I have something to say; that there is a relationship there where trust (with a capital T) is on everyone's forehead. That is what excites me about coming to Scotland. That is what excites me enormously about going to Berlin's Deutsche Oper [where he will be Music Director]. I can be myself. I feel that - and I don't want this to sound too pompous - I can let myself be a conduit where I can serve the music and where I feel that those musicians are happy that I'm there, want me there and that together we achieve something special. I am not a happy guest conductor. I need those relationships.

While you talk about Thielemann's old-fashioned playing, your own repertoire is quite old-fashioned too. Within opera it is pretty broad [left: San Fransisco Opera premiere of Doctor Atomic, conducted by Runnicles] but in the orchestral field it is focused on the late romantic repertoire. That is the repertoire that most people want to come to hear you in. And you seem happy to concentrate on it, whereas most other contemporary conductors often think that they can turn their hands to anything. What is your fascination with that period?

While you talk about Thielemann's old-fashioned playing, your own repertoire is quite old-fashioned too. Within opera it is pretty broad [left: San Fransisco Opera premiere of Doctor Atomic, conducted by Runnicles] but in the orchestral field it is focused on the late romantic repertoire. That is the repertoire that most people want to come to hear you in. And you seem happy to concentrate on it, whereas most other contemporary conductors often think that they can turn their hands to anything. What is your fascination with that period?I always have a fascination with that period because that is the period that most definitely got me into this profession in the first place. It was being immersed in the music of Richard Wagner which opened all sorts of unbelievable doors. In turn it lead to my fascination with Mahler, my reading Henry Louis de la Grange and finding out about this remarkable composer-conductor who worked in Germany, who would conduct in any given week maybe three of four different titles - say, Pique Dame, Hansel and Gretel and Lohengrin.

When I found out about that that certainly convinced me to seek the profession in Germany. All these doors kept opening up. It emanated from this source, this love, of the music of Wagner. I have literally, since I was a boy, been immersed in this music. I suppose I feel the most at home in that. Having said that, in the years that I was music director in San Francisco, I have had equal exposure to quite a bit of contemporary opera: the music of John Adams, Conrad Susa and Jennifer Higdon. I love that too. I threw myself into Adams's Doctor Atomic [above left] with verve. I do like to keep a broad-ish repertoire. In addition to that I was with the Orchestra of St Luke's in New York. The size of that orchestra meant we were somewhat limited in repertoire, and I focused on Mozart and Haydn. It was a privilege to work with those musicians whose music-making is extremely informed by early music practices. I can fully understand why Simon [Rattle] enjoys the nutritious diet of the Age of Enlightenment and taking these same programmes to Berlin. I think that's fascinating and we are always being required to question our motives for making musical decisions. While, yes, I relish that late romantic repertoire, in Berlin I will be very focused on Britten and Berlioz, the two great mavericks. I don't think I'm too narrow-minded in my focus.

Perhaps the pattern is that you seem to relish the big fantasy. You have a very quiet manner - you shed limelight, get on with it quite modestly - yet you have this penchant for doing these huge fantastical pieces like Gurrelieder and Tristan [right: his acclaimed BBCSO Tristan recording with Christine Brewer] and the Trojans. Is that a deliberate tension within yourself that you like exploring?

Perhaps the pattern is that you seem to relish the big fantasy. You have a very quiet manner - you shed limelight, get on with it quite modestly - yet you have this penchant for doing these huge fantastical pieces like Gurrelieder and Tristan [right: his acclaimed BBCSO Tristan recording with Christine Brewer] and the Trojans. Is that a deliberate tension within yourself that you like exploring?That's a very perceptive thing that you've just said... [Long pause.] There's really no conscious Jekyll and Hyde thing going on; you weren't being that dramatic but there is no a tension or conflict there. It's to do with the disciplines involved when you conduct in an opera pit, when your are in a sunken pit, where there is frankly no room for great flamboyance, there's no room for "Look at me, look at me," egoistical music-making. Many in the audience cannot physically see what you are doing down there. Yet the responsibility that you carry for any given performance with hundreds of musicians reliant on your ability to bring it all together and more. One is, as a conductor, far more focused on getting the job done. Because flamboyance serves no one. And musicians, singers and directors today are grateful for when a conductor is just there to coordinate and to, yes, serve the music but not to serve his or her personal agenda of how does this or that look etc. I have been lucky in having a fairly balancing professional life between the operatic and orchestral worlds, which is unusual certainly in the US, where there is a continental divide between two. When you come into symphony world and you are standing up there on the rostrum, my operatic life has informed my stick technique in as far as the focus is not on me but on the music. It isn't that I'm such a remarkably self-effacing modest guy. For anybody to stand up in front of any orchestra - next week I go to conduct the Berlin Philharmonic in repertoire that they can safely claim as their own - you have to believe in yourself, you have to have a very healthy ego. But ultimately I feel I'm there to serve the music. I just personally feel that this is something that musicians respect.

Do you conduct with a score or not?

I always conduct with a score. Because it never fails to happen that some detail will leap out out me. Where I will suddenly put two and two together and realise that there is something I've missed thematically. Of course you can pore over the scores in between rehearsals but it is very often in a performance that somehting will occur to me.

That would throw me. Does it not throw you?

I don't worry about it for exactly that reason: you have no idea what's going to happen. It's so much about what I'm about when I'm making music - and that's for others to like or dislike. If I'm in the opera house, it's still a miracle to me that you have a chorus of 200, an orchestra of an 100, hundreds of people, costume changes, off stage trumpets, and that it comes together. You don't know what's going to happen till it happens. For me conducting from memory can seem a little like press-the-print button. "I know what's going to happen; I know how it's going to work; I know to give this cue here and this cue here." They can be utterly brilliant performances but for me the danger is that I think about what I've memorised - "and then that happens and then that happens". I would feel that there's a level of spontaneity that I'm not open to channeling or tapping into for fear of getting something wrong. And as new details keep emerging from scores from me, I will continue to use a score. Not to mention the fact that conducting from memory makes orchestras incredibly nervous.

Really?

Oh yes. Incredibly nervous. The singers on stage when they see a conductor on stage without a score... I can mention to you many instances where, if the orchestra had not been very vigilant, a performance would have ground to a halt because of a missed cue or because something went wrong. This is not some personally grudge from me, but I think it is a very rare thing that somebody who has memorised a score is still completely and utterly free to give a completely different performance on any given night. There are some scores I quite frankly couldn't memorise. If I'm conducting Messiaen's Saint- François d'Assise - which I have - what's the point of memorising it. I couldn't memorise it anyway, but would I be freer? Am I able to give something more that having to look at the score prevents me from doing? I think a compelling case has to be made for it. Is anyone better off if it's done from memory? I remember Giuseppe Pattini, who used to come to Mannheim very often in the 1980s when I was there, to conduct Lohegrin, Cavalleria Rusticana, I Pagliacci, all from memory and with a nonchalance that was uncanny. I asked him once, "Why do you memorise all these scores?" He look at me and said: "Ah... all that baggage on the plane." I know it myself: if you're on the road for two months, you have to think about those 10 scores.

Was it exposing after being a repetiteur and opera conductor for so long, making the leap into the fresh air of orchestral conducting?

Initially, yes, I must say. All of a sudden, one felt a little self-conscious and exposed. It is a little like experiencing some singers who are just transcendent on stage and give their best performances because there's lighting, costumes, makeup, a narrative and then you see the same artist given a liederabend and all of a suddenly they look uncomfortable or you sense something uncomfortable because there's nowhere to hide. There's a certain similarity there that I experience certainly early on when I was debuting as an orchestral conductor.

When was your debut as orchestral conductor professionally?

That was back in the early 1980s, 1981 or 1982, when I was conducting youth orchestras like the Deutsche Philharmonie. 1987 I went to Hanover. I was about 31 or 32 when I first started orchestrally. But it really wasn't until I went to the States in 1993 and in 1994 to Seattle and Chicago that it became a more regular diet. So often I expected to go there and hear from somebody that I should stick to opera. But now I've gotten away with it for so long I must be doing something right.

This fascination with Germany and late Romantic music: did that come from spending time in Germany or did the Germanic bug come before the move?

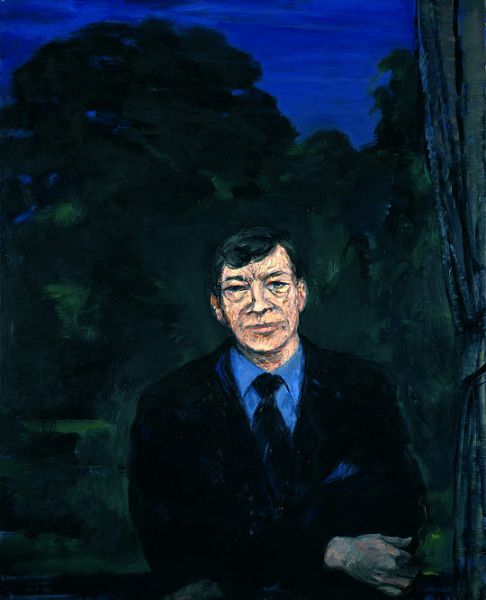

This fascination with Germany and late Romantic music: did that come from spending time in Germany or did the Germanic bug come before the move?The fascination with Germany came with the music of Richard Wagner. It was a seminal moment in my life. It was 1971 and with the school class, with an extremely enlightened music teacher, we went to Glasgow and saw Alexander Gibson's [left: portrait] Das Rheingold. And here's the biggest cliche of all time: the rest is history. That changed my life. I very much felt that there was a third dimension to this music; it was like sitting in the middle of some sound system. There was literally something visceral about it, as if you could touch one of those sonorities. That thrill has never left me. That's where I started feverishly learning all the Wagner operas and reading anything I could get about that man. It lead to many other composers who were enormously influenced by him. And I thought that if I really wished to entertain the thought of being a professional conductor the best thing to do would be to go to Germany and seek out that storied path: beginning as a repetiteur and working your way through the system.

I realised early on that it was important to speak the language. i worked very hard to be bilingual. The more I was working in Germany the more I realised I did have a talent for bringing the best out of people, bringing people together, creating good teams. That's when I first thought of being a music director, as opposed to a guest conductor or Kapellmeister. Because I enjoy bringing people together. I enjoy planning; I enjoy looking years ahead and talking repertory with directors, with scenic designers, choreographers, dramaturgs. I love the process. That should in no way sound arrogant. I just love doing that. Just last week I was speaking with David Pountney; we're doing the Trojans together next season in Berlin. We were emailing back and forth about possible cuts and rearranging numbers. I realised with what relish I was doing this. This is what i live for. This is where this whole love affair with Germany and opera began.

How did you get your first job in Mannheim [right]? Because I imagine they must have looked at you very strangely: this young presumptious Scot thinking he could come over and get a job just like that in the home of classical music.

How did you get your first job in Mannheim [right]? Because I imagine they must have looked at you very strangely: this young presumptious Scot thinking he could come over and get a job just like that in the home of classical music.Glorious follies of youth I guess. Twenty years on I probably would never have had the nerve to do it. What happened was that I went to the London Opera Centre - the precursor to the National Opera Studio - from 1977 to 1978 because I had made this decision to look to become a repetiteur and to see how far I could take it. Along with a colleague, we planned a trip to an agency in Munich in 1978 to audition. As you may know you don't just turn up at the opera house; the brokers are the agents. You play for them and they say, "You're very good; I am going to recommend that you audition for this job in Munich or Stuttgart or whatever." I went over there. I had not worked on my German and I was told that in no uncertain terms they thought I was not ready to start as a repetiteur. What they suggested was that I become a ballet repetiteur of one of the larger compoanies and on a surgagote level I would pick up about opera and I could move over to the opera hous. I said yes - I bit my tongue. I went to Mannheim. The ballet director said great, start. I began in fall of 1978 as the official ballet repetiteur at the National Theatre, Mannheim [above right].

What was incredible fortuitous about that was that in 1978 that opera house performed no less than 55 different titles every year. So obviously I was working with a large ballet company - I experienced all the major Stravinsky ballets there - and a different opera every night - that exposed me in a phenomenal way to opera. A colleague left his job at Mannheim opera. It become vacant. I auditioned for his job and I got it. I became opera repetiteur in 1979. That led to me becoming the music director's assistant. The music director encouraged me to do more conducting, he put me in front the of the orchestra on many occasions when he was off guesting and invariably all of those performances were without rehearsal. I had never stood up in front of the orchestra.

That was arguably the most profoundly important part of my training back then. It really was seminal. You are forced to express your wishes only through gesture. Your only means of persuasion is through your eyes. Your whole body language You cannot stop to say I wish to do this differently to the previous conductor, I wish to do this in two instead of four. All of this you have to show. That is something I recommend to all young conductors who poach me for advice. It's still the system to try o get into because you get a chance to work on yourself and you develop a glossary, a vocabulary of gestures where conducting is a bit like playing an instrument. You don't eventually think about the technique behind it, so you're just focused on making music. In order to do that you just have to conduct and conduct and conduct and conduct. That is what Mannheim afforded me.

But what must have been the pinnacle at this time of your career was to perform at Bayreuth? How did it feel to be asked to conduct there for the first time?

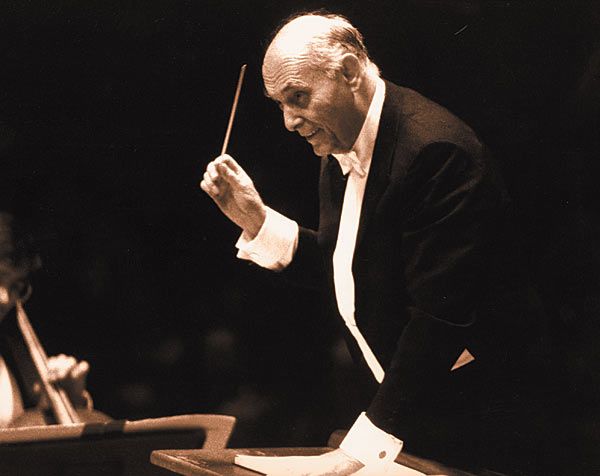

But what must have been the pinnacle at this time of your career was to perform at Bayreuth? How did it feel to be asked to conduct there for the first time?Extraordinary, yes. There was a feeling of: "It has all led to this." I had, however, experienced Bayreuth as an assistant to Jimmy Levine in 1992 for Parsifal. So I experienced the House as a pianist, as a repetiteur and as a coach. I auditioned for George Solti [left]. He was looking for an assistant for The Ring in 1983. I will never forget that audition, a very, very muscular strong hand on my shoulder making the pulse of the bar. He was extremely physical.

Did you get that job?

Yes. The other members of the music staff included David Syrus and Tony Pappano. We were all on this work together. While we were working on the Ring with Solti in Bayreuth, a young Thieleman was working with Barenboim too. This is when we all got to know one and other. I worked with Peter Schneider when he took over from the ailing Solti. I had about 6 years where I was one of their pianists and repetiteurs. I knew the house very well indeed, so when I was approached to conduct I did know of the remarkable but not unproblematic idiosyncrasies of that house. For example, what you hear in the pit as opposed to what your hear in the house etc. Undoubtedly, a pinnacle of my career has been those years I conducted there.

You must have become pretty spoilt in Germany, too, in terms of audiences and conducting. German audience are after all unparalleled in terms of knowledge and pack out houses every night. It must have been very different elsewhere.

You must have become pretty spoilt in Germany, too, in terms of audiences and conducting. German audience are after all unparalleled in terms of knowledge and pack out houses every night. It must have been very different elsewhere.Yes, certainly the years where I was conducting primarily in Germany I began to take for granted that opera and symphonic music is literally front page news. Music and culture does play an intrinsic part of a city's life. The plethora of opera house and small symphony orchestras in germany is still remarkable. Each and every town is somehow proud of their artistic community and institutions. An audience in Mannheim is one that can drive in any direction for one hour and hit another six opera houses. In that sense there is a degree of sophistication in audiences which makes for a very interesting comparison when you come to, as I did, San Fransisco [right: San Fransisco Opera House]. The dimensions are all considerably larger. When I came legends had sung and conducted here. At the same time, very often you would be conducting or performing a work where you could be assured that many in the audience were seeing it for the very first time. And I'm talking about Jenufa, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk even Cosi fan Tutte. As an artist here, one is far more of an ambassador because you have that thrill of thinking that you're introducing a generation for the very first time to a work that has already established as a staple piece of the repertoire. There's something to be said of both.

A few years back, you got into some trouble for saying that you would consider leaving America if Bush won a second election.

Yes.

What happened there?

Oh, we lost a lot of donors in Atlanta [Runnicles was principal guest conductor with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra from 2001-09]. And I got an unbelievable amount of hate-mail: mother-f***ing this and mother-f***ing that. That was as a result of an interview I gave to the Salzburger Nachrichten. I was doing a production of Die Tote Stadt in Salzburg. We talked about that blah blah blah. Apparently the microphone was off, he said, "Now off the record: how was it living in America?" This was when we had embarked on the Iraq war in 2004, where I said that I was appalled by the way it had been rammed through the agenda. And my thoughts on Bush and Iraq, he asked. I said that California was my adoptive country and that, if George Bush were to be re-elected, for me, a population can make a mistake once but a second mistake would be telling the world that they indeed do want George Bush and that I would have to consider - consider - whether I would keep my children in California.

Were you ever front page news in Germany?

I made it - and for the right reasons. It was my appointment; I had been repetiteur and I was appointed to the first Kapellmeister, which was second chief conductor and that was a significant appointment and that did receive good coverage. And it was in those few season where I was Kapellmeister - I added this up; I knew one day I would look back on this and think, "What? I conducted how many concerts?!" - in my penultimate season I conducted 116 performances. I was conducting every second night. Once again, it's not about quantity, hopefully, but aout quality. What it did give me was this unprecedented repetition where conducting was like talking or moving. It becomes second nature. When I speak with young conductors here in America, I see a certain self-consciousness. I still see that hanger in the suit, so to speak, because, there, chances are so few and far between. You feel as if technique is still something that they are thinking consciously about. That's because they get on a bicycle three times a year and every time it's going to be hard.

The Scottish classical music scene is different from Germany too. It's a pretty safe bet that music won't be front page news in Scotland.

I have to correct you there. What Michael Tumelty has achieved in the extent to which the Glasgow Herald is willing to let him achieve it, in terms of two articles a week, I think is extraordinary. Considering that there are many big cities in American that no longer have any kind of art or music critics. It's still a very healthy scene there when it comes to music criticism.

Your tenure with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra is going to have to be a sort of a guest conducting job because of all the time you will have to spend in Berlin. But you said you don't enjoy that.

I should clarify by what I mean by guest conducting. It's not the regularity with which one works with an orchestra it's the relationship which you've established early one. For me when I think of guest conducting, I'm talking about when you conduct the orchestra like a butterfly flitting from one to another. There are many orchestra who legitimately enjoy that life style. I know that when I conducted the BBCSSO back in 2001 for the very first time - it's hard to describe in words - there was a chemistry that was apparent to all of us within a very short period of time. We were speaking the same language. Our approach to music was similar. And it felt that this orchestra became an extension of my own musical personality. Back then there were no discussion about any kind of music directorship except that I would be able to work every year or second year with the orchestra. In that very first concert of Berlioz's The Trojans, at Edinburgh, it was clear there was something special going on between us. With relationships like that, there's no guarantee that the relationship would work. But when it does work you're onto something special. Even though it's 10 or 11 weeks a year with the BBCSSO, there is a trust between us that makes every weekend very special.

So where was Runnicles [left]? I mean why were you absent from Scotland and Scottish music making for so long. Were you avoiding Scotland or were they avoiding you?

So where was Runnicles [left]? I mean why were you absent from Scotland and Scottish music making for so long. Were you avoiding Scotland or were they avoiding you?I certainly have never felt that there has been a problem there. In all fairness, I know that I had often been asked to conduct in Scotland and simply because my calendar extends fairly far forward, enquiries from Scotland would by necessity be relatively late. It was just too short term for me to say yes. It would have been a very large time commitment for me which I could not commit. That is not to insinuate that I was ignored. Not at all. Neither though did I think, while away, that I am going to give Scotland wide birth. My career began in Germany; I was extremely busy in Germany. It was then in Austria, then in America. I have had a very fulfilling life and there just didn't happen to be any engagements form Scotland. It's not for me to say but I dont' think anyone had a problem with me. Out of sight, out of mind. The fact that my appearances in Britain were few and far between meant that I was not on people's radar. San Francisco, no matter how globally intertwined we all are, is still hell and gone - a long long way away!

I think that my career is at a point where I have chosen to make Europe more the focus of my life and events have conspired to bring all this together where a relationship with both Berlin and Glasgow-Edinburgh works. I don't in any way feel like a prodigal son, however. I know there are these buzz words. I see the editor chasing a headline there. I don't think any of those are appropriate. There's no sour grapes there. It's just I have chance to build on a relationship with a great orchestra with great people. As I said before, I feel I have been given the opportunity to make a difference and I embrace that wholeheartedly.

Share this article

more Classical music

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

Bell, Perahia, ASMF Chamber Ensemble, Wigmore Hall review - joy in teamwork

A great pianist re-emerges in Schumann, but Beamish and Mendelssohn take the palm

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Persons: composers Colin Alexander and Héloïse Werner on fantasy in guided improvisation

On five new works allowing an element of freedom in the performance

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

First Person: Leeds Lieder Festival director and pianist Joseph Middleton on a beloved organisation back from the brink

Arts Council funding restored after the blow of 2023, new paths are being forged

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Classical CDs: Nymphs, magots and buckgoats

Epic symphonies, popular music from 17th century London and an engrossing tribute to a great Spanish pianist

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Philharmonia Chorus, RPO, Petrenko, RFH review - poetic cello, blazing chorus

Atmospheric Elgar and Weinberg, but Rachmaninov's 'The Bells' takes the palm

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Daphnis et Chloé, Tenebrae, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - lighting up Ravel’s ‘choreographic symphony’

All details outstanding in the lavish canvas of a giant masterpiece

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Goldscheider, Spence, Britten Sinfonia, Milton Court review - heroic evening songs and a jolly horn ramble

Direct, cheerful new concerto by Huw Watkins, but the programme didn’t quite cohere

Marwood, Power, Watkins, Hallé, Adès, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - sonic adventure and luxuriance

Premiere of a mesmeric piece from composer Oliver Leith

Marwood, Power, Watkins, Hallé, Adès, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - sonic adventure and luxuriance

Premiere of a mesmeric piece from composer Oliver Leith

Elmore String Quartet, Kings Place review - impressive playing from an emerging group

A new work holds its own alongside acknowledged masterpieces

Elmore String Quartet, Kings Place review - impressive playing from an emerging group

A new work holds its own alongside acknowledged masterpieces

Gilliver, LSO, Roth, Barbican review - the future is bright

Vivid engagement in fresh works by young British composers, and an orchestra on form

Gilliver, LSO, Roth, Barbican review - the future is bright

Vivid engagement in fresh works by young British composers, and an orchestra on form

Josefowicz, LPO, Järvi, RFH review - friendly monsters

Mighty but accessible Bruckner from a peerless interpreter

Josefowicz, LPO, Järvi, RFH review - friendly monsters

Mighty but accessible Bruckner from a peerless interpreter

Cargill, Kantos Chamber Choir, Manchester Camerata, Menezes, Stoller Hall, Manchester review - imagination and star quality

Choral-orchestral collaboration is set for great things

Cargill, Kantos Chamber Choir, Manchester Camerata, Menezes, Stoller Hall, Manchester review - imagination and star quality

Choral-orchestral collaboration is set for great things

Add comment