John le Carré: A Legacy of Spies review - the master in twilight mood | reviews, news & interviews

John le Carré: A Legacy of Spies review - the master in twilight mood

John le Carré: A Legacy of Spies review - the master in twilight mood

George Smiley re-encountered in a tale of tainted legacies

Over his long career – 23 novels, memoirs, his painfully believable narratives adapted into extraordinary films (10 for the big screen) and for television – John le Carré has created a world that has gripped readers and viewers alike.

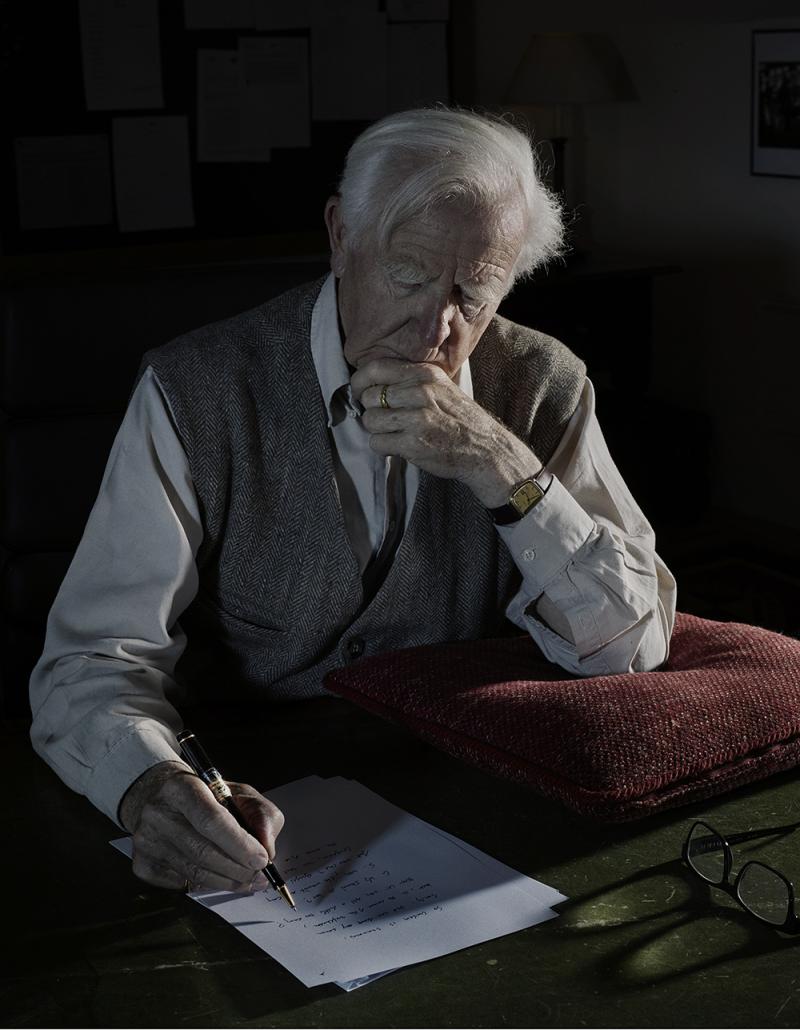

Now in his mid-eighties, he published the mesmerising memoir The Pigeon Tunnel last year. He is, of course, a master raconteur: commenting on that absorbing autobiography, critics tried (and mostly failed) to figure out fact from fiction, although all was presented as real. Some salient biographical facts are key to the mystique: the bankrupted father, a charming conman; a stint as a teacher at Eton; and a period in various sections of British intelligence. But from his early thirties onwards, for more than half a century now, he has been the writer, the master story-teller of Europe, of spies and politics, alliances and allegiances, of the Cold War icing up and thawing; and, more recently, of politically corrupt and criminally unethical shenanigans in various corporate worlds. He writes fiction – and history.

The old master is now up to tricks both old and new. He has returned to a world which, however complex, was predicated on the Cold War, Russia and her satellites in Eastern and Central Europe against the West, Europe and the United States. And it is a return to the period and characters of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. It is no accident that the narrator, Peter Guillam, is also an octogenarian, recruited as a very young man into the intelligence services (as was le Carré): his past is much like that of his creator. Underlying this delicately bitter book is the uneasy feeling that all was for naught – the pain and sacrifice, the grey areas between whatever might be right and wrong, the ends justifying the means, or not (when the means on both sides of the great divide were all too similar).

The old master is now up to tricks both old and new. He has returned to a world which, however complex, was predicated on the Cold War, Russia and her satellites in Eastern and Central Europe against the West, Europe and the United States. And it is a return to the period and characters of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. It is no accident that the narrator, Peter Guillam, is also an octogenarian, recruited as a very young man into the intelligence services (as was le Carré): his past is much like that of his creator. Underlying this delicately bitter book is the uneasy feeling that all was for naught – the pain and sacrifice, the grey areas between whatever might be right and wrong, the ends justifying the means, or not (when the means on both sides of the great divide were all too similar).

We alternate between past and present. le Carré is angry about the world as it is now, symbolised too by London: he is overtly critical of the present, of the overpowering new headquarters of the intelligence services on the Thames, rather than the ramshackle ungentrified Bloomsbury of the past.

This novel is concerned indeed with a legacy of past actions, an inheritance, a tainted one. As its title indicates it is elegiac, the past visibly informing the present. Guillam has appeared before as a gofer protégé of George Smiley, the short, pudgy character who is the best-known of all of le Carré’s creations. The novel operates both in the present and in flashbacks to operation Windfall, in Germany and Eastern Europe, that took place in the period when the author himself worked in the secret services.

There is hardly a single sentence in this relatively short novel that is not quotable, and the opening paragraph, one single, long, beautifully choreographed sentence, quietly seizes the reader and just won’t let go. “What follows is a truthful account, as best I am able to provide it, of my role in the British deception operation, codenamed Windfall, that was mounted against the East German Intelligence Service (Stasi) in the late nineteen fifties and early sixties, and resulted in the death of the best British secret agent I ever worked with, of the innocent woman for whom he gave his life.” Guillam, long retired to his Breton farm, is the narrator of what follows, told in both the past and historical present tense.

The sacrifices were for a cause now forgotten, and the purpose was for Europe

The trigger for the interplay between past and present is the adult children of those who died: Alec Leamas and Liz Gold, murdered at the Berlin Wall, leaving behind unknown children whom they did not raise. Now they, Christoph and Karen, are approaching the British government for compensation (le Carré makes no secret of his disgust at the 21st century blame game for events long past).

Guillam is summoned back to London, and to account. Back to the Stables, a safe house in Bloomsbury that houses the Library, the stolen files of the operations of the 1950s and 1960s, especially Windfall, which Guillam (irritatingly called Pete by one of his minders) is being forced to read under close observation. The memos and reports he looks at are printed in a tighter layout from the prose describing past and present, so the reader easily distinguishes between apparently real events and the ways in which they were reported. In between the Stables and bedding down on a painfully austere single bed in a minimally inhabitable safe flat in Dolphin Square, Peter wanders London.

The documents he reads recall his exquisitely painful attachment, mostly in the mind, to the seductive East German who was both wife to a spy and coerced mistress to her Stasi boss, a turned double agent, code-named Tulip. The events of the past embedded in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy are touched on from multiple viewpoints, but you do not need to know these earlier novels to know what is being illuminated by twisted betrayals. Underlying all is the pained search for a very high-up mole and double agent in the British intelligence services. The rivalries in the Circus itself, between the top at Joint Steering, and those in Covert, run by Control and George Smiley, are part of the mix. The reader is given more of a map than the novel’s heroes and anti-heroes.

Throughout there is the sense of the betrayal of the past by the present, crystallised in an extraordinary and affecting encounter, an open-ended conclusion, with Smiley, tracked down by his foot soldier Peter to a research library in Freiburg. The sacrifices were for a cause now forgotten, and the purpose was for Europe: “If I was heartless, I was heartless for Europe. If I had an unattainable ideal, it was of leading Europe out of her darkness towards a new age of reason.” Post-Brexit, indeed. A Legacy of Spies seems like a valedictory novel: we can only hope there may be more.

- A Legacy of Spies by John le Carré (Viking, £20)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

more Books

Heather McCalden: The Observable Universe review - reflections from a damaged life

An artist pens a genre-spanning work of tender inconclusiveness

Heather McCalden: The Observable Universe review - reflections from a damaged life

An artist pens a genre-spanning work of tender inconclusiveness

Dorian Lynskey: Everything Must Go review - it's the end of the world as we know it

Authoritative account of how the apocalypse has always been just around the corner

Dorian Lynskey: Everything Must Go review - it's the end of the world as we know it

Authoritative account of how the apocalypse has always been just around the corner

Andrew O'Hagan: Caledonian Road review - London's Dickensian return

Grotesque and insightful, O’Hagan’s broad cast of characters illuminates a city’s iniquities

Andrew O'Hagan: Caledonian Road review - London's Dickensian return

Grotesque and insightful, O’Hagan’s broad cast of characters illuminates a city’s iniquities

Annie Jacobsen: Nuclear War: A Scenario review - on the inconceivable

Brimming with terrifying facts and figures, but struggling with an immeasurable subject

Annie Jacobsen: Nuclear War: A Scenario review - on the inconceivable

Brimming with terrifying facts and figures, but struggling with an immeasurable subject

Anna Reid: A Nasty Little War - The West's Fight to Reverse the Russian Revolution review - home truths

Reid brings to light a war the West has tried its best to forget

Anna Reid: A Nasty Little War - The West's Fight to Reverse the Russian Revolution review - home truths

Reid brings to light a war the West has tried its best to forget

Tom Chatfield: Wise Animals review - on the changing world

A compelling account of how we use technology – and how it uses us

Tom Chatfield: Wise Animals review - on the changing world

A compelling account of how we use technology – and how it uses us

Sheila Heti: Alphabetical Diaries review - an A-Z of inner life

Heti goes far beyond a gimmick in this work of surprising and moving insight

Sheila Heti: Alphabetical Diaries review - an A-Z of inner life

Heti goes far beyond a gimmick in this work of surprising and moving insight

David Harsent: Skin review - our strange surfaces

A fine poet pens a set of resilient expressions and elegant introspections

David Harsent: Skin review - our strange surfaces

A fine poet pens a set of resilient expressions and elegant introspections

Brian Klaas: Fluke review - why things happen, and can we stop them?

Sweeping account of how we control nothing but influence everything

Brian Klaas: Fluke review - why things happen, and can we stop them?

Sweeping account of how we control nothing but influence everything

Richard Schoch: Shakespeare's House review - nothing ill in such a temple

Scholar makes the Bard's house a home in his history of dramatic domesticity

Richard Schoch: Shakespeare's House review - nothing ill in such a temple

Scholar makes the Bard's house a home in his history of dramatic domesticity

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

Best of 2023: Books

As the year draws to a close, we look back at the best books we opened

Best of 2023: Books

As the year draws to a close, we look back at the best books we opened

Add comment